With summer officially here, it’s a great time to explore the outdoors! As people go hiking, camping, wildlife viewing and engage in other recreation activities, there can be associated impacts on the natural environment.

In 2017, more than 330 million people visited national parks alone, with millions more visiting state parks, wildlife refuges and federally designated wilderness areas as well.

United States Geological Survey scientists are working with many partners to study how these visitors are affecting protected natural areas. Some of the impacts include trampling of native vegetation causing erosion of soils, contaminating water, attracting wildlife with food and displacing wildlife from preferred habitats. “We’re doing research on the impacts people are having while they are out having fun in our nation’s wilderness,” said Jeffrey Marion, a USGS research ecologist. “The information we gather helps land managers make the best decisions on how to accommodate more visitors while limiting their overall impact, helping preserve protected natural areas for all generations to enjoy.”

Pristine campsite at Thousand Island Lake along the Pacific Crest Trail in California. Pristine campsite at Thousand Island Lake along the Pacific Crest Trail in California.

Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS

Camping

One of the major issues associated with camping is the common practice of cutting down trees for firewood. A USGS study of campsites in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness of northern Minnesota found that 44 percent of campsite trees had been damaged and approximately 18 trees per campsite had been cut down, primarily for firewood. This significantly alters natural environments, especially wildlife habitat.

“With 2,000 campsites in Boundary Waters, that’s approximately 36,000 tree stumps in a single wilderness area,” said Marion. “Understanding the effects that campers are having on the area can help rangers develop strategies on the best way to prevent further tree loss and explore options for recovery.”

USGS scientists are also examining what influences the expansion of campsite size and creation of new and unnecessary campsites. One significant factor is topography. Campsites in large, flat areas are frequently expanded by campers, which can cause more water runoff with soil and pollutants into lakes and creeks. Campsites in sloping terrain can still have sufficient flat areas for tents, but are smaller, will likely resist future expansion and will have less impact than larger campsites.

Runoff and pollution from campsites can degrade aquatic environments, leading to impacts such as decreased water clarity and purity. These have the potential to affect trout reproduction, as sediments carry fungus and bacteria that harm trout eggs. Sediments also introduce nutrients that cause algal blooms in water, diminishing the amount of dissolved oxygen that’s critical to fish survival.

The USGS has begun a study on the Pacific Crest Trail to identify the most sustainable campsites and develop online maps for easy navigation to those locations. Visitors will be able to print the maps or download them to a smartphone app or GPS device, and accompanying tips will be provided on low-impact camping suggestions.

Trees cut down for firewood in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in northern Minnesota. Trees cut down for firewood in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in northern Minnesota.

Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS

Low-impact Outdoor Practices

USGS science is used by many organizations to develop and communicate low-impact outdoor practices. Organizations include the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics and federal land management agencies, such as the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Based on USGS science, some low-impact outdoor practices communicated by land managers include visitors collecting only dead and fallen campfire wood that they can break by hand; choosing small campsites in sloped areas that are more than 200 feet from water; and concentrating activity on durable surfaces like rock or areas that lack plant cover.

Hiking Trails

Most visitors to protected natural areas hike on trails created with hardened treads designed to sustain traffic. However, heavy hiking traffic and use by mountain bikers, motorized vehicles and horseback riders all take their toll. Parks are also becoming more crowded, with long lines of trail users during the popular summer season. More visitors have been venturing off trails, trampling and removing protective vegetation and organic materials. This can compact soils and increase water runoff and erosion. Soil loss is the most significant and long lasting environmental impact.

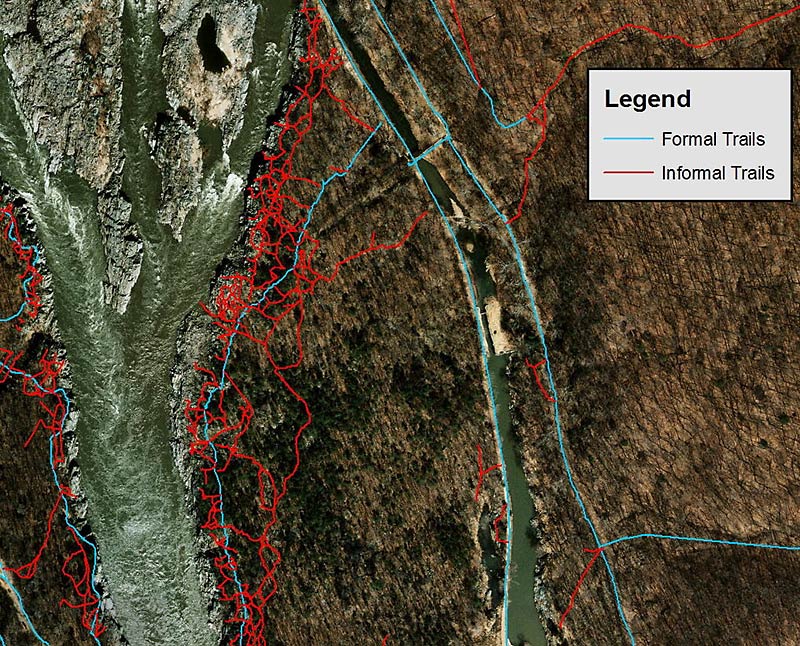

To address this issue, USGS scientists are collaborating with university social scientists to investigate sustainable trail design guidance and actions to deter off-trail hiking. As an example, a study was conducted to protect large numbers of rare plants near the Billy Goat Trail in Washington, D.C. In the study, scientists tested various communication methods at formal trailheads and at informal trails created by visitors -- including “don’t walk here” signs and placement of organic materials, such as leaves -- to hide and discourage use of the informal trails.

Another study area was Cadillac Mountain at Acadia National Park in Maine, where visitors have trampled fragile subalpine soils and vegetation on the summit. The USGS provided the science in support of a collaborative effort to develop best management practices, with recommendations that included educational signs and low fencing along trail borders. Research findings identified the most effective educational messages and suggested that the formal trail be extended and widened, with short side-trails to the most scenic spots.

USGS research is investigating factors that affect the sustainability of trails to support heavy hiking and horse traffic like in this scene taken along the Pacific Crest Trail in Yosemite National Park in California. USGS research is investigating factors that affect the sustainability of trails to support heavy hiking and horse traffic like in this scene taken along the Pacific Crest Trail in Yosemite National Park in California.

Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS

Feeding Wildlife

Wildlife feeding, intentional or unintentional, is common in many national parks and protected areas. This can lead to food attraction behavior, where animals start to associate food with people, sometimes putting dangerous animals, or those that spread disease, in close proximity to humans. But the practice is also harmful to wildlife, which can suffer nutritionally, become dependent on unreliable food sources and become more susceptible to predators, dogs and vehicle accidents.

USGS science has helped land managers develop effective visitor messages to deter wildlife feeding. As an example, a study conducted on the popular Angel’s Landing Trail at Zion National Park in Utah looked at the issue, focusing on chipmunks. Educational messages were provided through signs or delivered personally by uniformed park staff. Messaging significantly reduced the instances of visitors feeding wildlife.

Education

The USGS works with the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics to provide science that underpins the development and evaluation of best practices as well as educational courses and materials. Those resources have been widely adopted by federal, state and local managers of protected areas and numerous outdoor organizations. The book, “Leave No Trace in the Outdoors,” which is authored by Marion, discusses ways to enjoy the outdoors while minimizing environmental and social impacts.

Start with Science

“With so many people visiting and enjoying the great outdoors and exploring the wonders of nature off the beaten path, leaving no trace can be a real challenge,” said Marion. “But our science can inform decisions being made across the landscape to help prevent, minimize or mitigate the effects some recreational activities are having on our wildernesses.”

USGS research documented these informal trails created by off-trail visitor traffic in areas with large numbers of rare and endangered plants in Potomac Gorge near Washington, DC. Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS USGS research documented these informal trails created by off-trail visitor traffic in areas with large numbers of rare and endangered plants in Potomac Gorge near Washington, DC. Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS

USGS scientist Jeffrey Marion and Virginia Tech student Holly Eagleston measuring conditions at the Appalachian Trail in Virginia to evaluate trail impacts and sustainability guidance. USGS scientist Jeffrey Marion and Virginia Tech student Holly Eagleston measuring conditions at the Appalachian Trail in Virginia to evaluate trail impacts and sustainability guidance.

Credit: Matthew Browning, Virginia Tech Graduate Student, College of Natural Resources and the Environment

USGS research revealed that these educational symbolic signs were highly effective in deterring off-trail hiking that was threatening rare plants in Potomac Gorge near Washington, DC. Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS USGS research revealed that these educational symbolic signs were highly effective in deterring off-trail hiking that was threatening rare plants in Potomac Gorge near Washington, DC. Credit: Jeffrey Marion, USGS

Note: This story and images were provided to High On Adventure by the United States Geological Survey. Contacts are Jessica Fitzpatrick ([email protected]) and Jeffrey Marion ([email protected]) Visit their website for more information: https://www.usgs.gov/about/organization

|