JULY/AUGUST 2021, OUR 25TH YEAR

LIVING MEMORIAL SCULPTURE GARDEN Where War Veterans are Remembered |

||

Story and photos by Lee Juillerat |

Veterans remembered at Sculpture Garden

It’s hidden off a well-traveled highway, set in a forest of pine and fir trees in a remote region of far Northern California. It’s a place that can be visited in just 10 minutes, but the Living Memorial Sculpture Garden is also a place where the memories of a visit will linger much longer.

The Living Memorial Sculpture Garden isn’t just another roadside attraction. Located off Highway 97 south of Oregon between the California communities of Dorris and Weed, the Sculpture Garden is a place to pause and reflect. The 11 metal sculptures are purposely designed to convey moods and expressions for the ages.

Peaceful Warrior at entrance

The idea for the garden began in 1987 when Ric Delugo, a Vietnam veteran and artist, promoted the idea of combining sculptures with a forest grove of 58,000 trees, one for each U.S. armed forces member who died in the Vietnam War. The concept seemed crazy, but Delugo attracted like-minded supporters, including sculptor Dennis Smith, another Vietnam veteran.

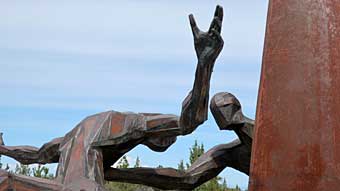

One of the faceless sculptures

Their vision resulted in a unique “garden” of faceless sculptures on 136 acres of Forest Service lands. Quickly, the garden grew to include additional sculptures that commemorate veterans of the Korean War and World War II – from nurses to prisoners of war, soldiers listed as missing in action, others wounded and those left behind. The sculptures are intentionally faceless, abstract, androgynous and, 35 years later, still contemporary. None feature glorified warriors. None inspire jingoist chest-pounding. Some sculptures express the pain of loss, others celebrate peace and the joy of being alive and at home. |

|

“Through the arts we have the means to peacefully consider violence and to ask questions as well as to offer possible solutions,” Smith explains in the brochure about the garden. “I don’t think the purpose of art is to entertain, but to uplift, edify and educate.”

"If you're trying to make a statement of forever, you have to have a time-line," deLugo explained of Smith’s sculptures. "Dennis' expression comes through the hands. The rest of it he kind of left androgynous, contemporary, abstract, almost asexual."

Smith's creations, all executed in 14-gauge steel using 3/16-inch welding rod, are especially poignant in a forested setting under the omnipresent presence of Mount Shasta.

"Each sculpture has a personal meaning for me in terms of life experience and personal incidents,” Smith continues in his brochure. “Everyone who has experienced war seems to have a place in their collective heart that is malfunctioning. Maybe what we should do is find that place in the heart and have it surgically removed. Through the arts we have the means to peacefully consider violence and to ask questions, as well as offer possible solutions."

|

Among the sculptures is "The Why Group," which features a larger-than-life sculpture that was intentionally designed as the Garden's first piece. The top-most of three figures beseechingly flings his arms skyward. As Smith explains, “After all the deeds are done and the soldier goes back home, sits alone in front of a warm fire on a cold night having the time to think his own thoughts, he may ask himself a few questions. 'Why me?' ‘Why not me?' 'Why him and not me?' 'Why war? 'Why not war?' The WHY questions are endless," Smith says. Poignant, too, was "The Refugees," a line of 17-foot-tall and shorter people on a metallic slab-like wall that has since been removed because of vandalism. Smith said it was his attempt to remember the timeless victims of war. A one legged-man using a walking stick led the sad march. While his inspiration comes from refugees he saw while serving in Vietnam, Smith said believes in their universality. "I was also thinking of the Kurdish people during the Gulf War, and the treatment of the Native American in 'The Long Walk' or 'Trail of Tears,'” he said during an interview. |

|||

“Why” sculpture |

|

||||

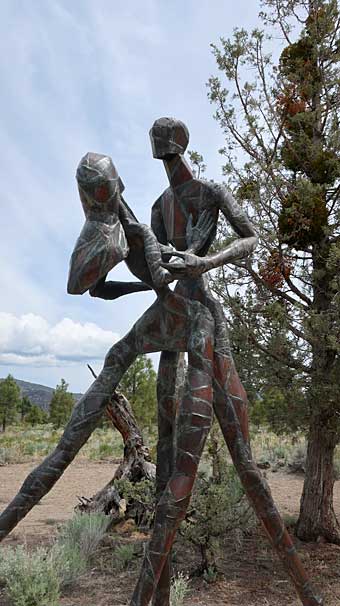

‘Peaceful Warrior’ greets visitors |

|

||||

‘Flute player’ |

|

|

Other works are more optimistic, including "The Peaceful Warrior," which greets visitors at the park's entrance. Ironically, and somewhat symbolically, passersby have fired bullets in the chest, stomach and thigh. "The Flute Player" symbolizes peace and tranquility, while "Coming Home" embraces the passion of a couple rejoined.

Other sculptures include "Those Left Behind," which is what its name indicates. "The Nurse" remembers those who helped the dead and dying. The "Hot LZ Memorial Wall," includes a sculpture remembering helicopter pilots in a hot landing zone. Another sculpture is the aptly titled "Korean War Veteran Monument." |

|

|

|

|

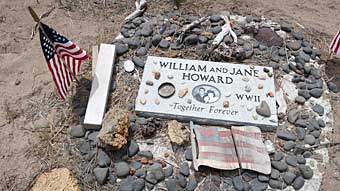

But possibly the sculpture packing the most impact is "POW-MIA," a statute of man imprisoned within a small cage. Visitors have left behind dog tags, small U.S. flags, POW bracelets and tokens at the prisoner of war statue.

|

|

Visitors leave tokens behind

Each year, two memorial services are held at the Garden - one on Memorial Day in May and another on Veterans’ Day each November. At the services, new names are placed on the Hot LZ Wall. Each name inscribed is of a veteran of the U.S. military and allied forces. Virtually, every war and conflict that the United States has been involved in is represented by names of service personnel. As the board of directors emphasize, the Sculpture Garden is not only for veterans but for everyone because “we are all affected by conflicts in this world. Although we may not be the soldier, sailor, marine or airman engaged in a conflict, we may be a family member left behind, or the refugee whose home has been torn up by the ravages of war.”

|

As those who oversee the Garden so aptly explain, “The Living Memorial Sculpture Garden is a place for contemplation and reflection upon the valiant efforts of human beings to make this world a more peaceful place in which to live. To their sacrifice, this place is dedicated.”

Getting There

The Living Memorial Sculpture Garden is located off Highway 97 and is 13 miles north of Weed, California and 38 miles south of Dorris, California, near the A-12 cutoff road. From Klamath Falls, Oregon, the distance is 71 miles east while the distance from Medford, Oregon, northwest is 79 miles. An information booth with brochures is near the entrance. A one-way road passes two sculptures before reaching a parking area with easy walking access to several other sculptures. There is no admission fee for the area, which is open dawn to dusk. For information visit the Website at www.lmsgarden.org. The site has information on becoming a lifetime member, with the named engraved on the Gene Breceda Sponsor Wall, or an annual membership.

A place to reflect

| About the Author Lee Juillerat is a semi-retired reporter-photographer who lives in Southern Oregon and is a frequent contributor to several magazines and other publications. He has written and co-authored books about various topics, most recently "Ranchers and Ranching: Cowboy Country Yesterday and Today.” Lee has produced photo-stories about U.S. and worldwide travels in High On Adventure for more than 20 years and has written about the Living Memorial Sculpture Garden since it opened in 1988. He can be contacted at [email protected]. |

|

|||